Ukraine and Trump's Failure to Protect Our Allies!

October 17, 2025

WritTrump LOSES IT at DISASTER WH Meeting with ZELENSKY

h, 5.48M subscribers., Oct 17, 2025 The MeidasTouch Podcast

MeidasTouch host Ben Meiselas reports on the disastrous meeting in the White House between Trump and Zelenskyy that was captured on live tv for the entire world to see. Mando: Control Body Odor ANYWHERE with @Shop.Mando and get 20% off sitewide + free shipping with promo code MEIDAS at https://shopmando.com! #mandopod Visit https://meidasplus.com for more!

September 25, 2025

Is WW3 Breaking Out?

Millions Protest Putin in Moscow Streets — Then THIS Collapse Shook Everyone

, 2.72K subscribers. 377,050 views Sep 24, 2025 #RussiaProtests #PutinCrisis #MoscowUnrest

Please help me get to 100,000 subscribers: / @russia_in_chaos Moscow is erupting as millions flood the streets against Putin, empty shelves and fuel lines stretching for miles. Ukraine’s strikes are shaking daily life inside Russia, and the Kremlin’s grip is slipping. Is this the beginning of Russia’s collapse—or the moment the world changes forever? 0:00 Russia on Fire: Millions Rise Against Putin 2:13 Collapse of a 25-Year Regime 5:25 Protests Turn Into Nationwide Escalation 9:04 Economic Meltdown and Military Strain 13:13 Global Shockwaves of Russia’s Crisis 17:17 Russia at the Edge of History Disclaimer: • This video is for informational, educational and commentary purposes only, not intended to promote, encourage or incite violence or armed conflict., • All images and materials used are for illustrative purposes only and may be compiled from many public sources., • The video content is intended to help viewers better understand history, politics, military and international events, and does not represent any organization, government or individual., • The channel is not responsible for any actions that misinterpret the video content., Thumbnail Disclaimer: • The thumbnail is for visual illustration purposes only and does not accurately reflect the actual image of the event., • The graphic details, effects or simulated images, if any, are for visual and educational purposes only and are not intended to spread false information., • The thumbnail does not represent any country, organization or individual. #RussiaProtests, #PutinCrisis, #MoscowUnrest, #UkraineWar2025, #GlobalSecurity

BREAKING: Russia Says NATO Has DECLARED War; US Military ORDERS Major Meeting | EnforcerNews

,500K subscribers, Premiered 89 minutes ago

This morning, Russian officials say NATO & The EU have declared war on Russia as Russia ramps up a series of major escalations today against the alliance. We also have unprecedented news that the U.S. has ordered virtually all top military leadership to gather at a military base in Virginia for some unknown reason. (Just for context, this has never happened before). Meanwhile, Russia has sent fighter jets to buzz Alaskan & Latvian airspace today. They have also begun to aggressively “pursue” German satellites in orbit, and more drones have been spotted over Denmark. And while all that is happening, NATO says it is preparing to shoot down Russian fighter jets as Russia warns that will start world war 3 instantly and they threaten consequences. Please like and subscribe for more daily short-war videos. Make sure to support us on Patreon so we can keep covering news like this! / the_enforcer Join The Enforcer's Twitter: / itstheenforcer Support The War Effort: https://u24.gov.ua/...

BREAKING: Hegseth SCRAMBLES Top Generals To Secure Location

, 201K subscribers, Sep 25, 2025

David Hookstead talks about Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth recalling top military leadership to a secure location in Virginia. What is happening? Comment with your thoughts, and make sure to like and subscribe! You can follow David Hookstead at the following: Instagram: @david_hookstead Twitter: @dhookstead Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/0K13bLi... Apple podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast... Chapters: 00:00 Intro 1:52 The World Is On Fire 3:06 Hegseth Recalls Top Military Leaders 7:07 What Is Going On? 8:16 Is War Happening?

September 22, 2025

Russia-Ukraine War: Over Three Killed & Dozens Injured In Latest Russian Missile Raids | WION

, 10.1M subscribers

Russia issues an ominous warning to Western forces | 9 News Australia

, 1.73M subscribers, 25,765 views Sep 5, 2025 #9News #BreakingNews #NineNewsAustralia

Vladimir Putin has issued a warning that any Western forces that set foot inside Ukraine will become a legitimate target for Russian forces | Subscribe and 🔔: http://9Soci.al/KM6e50GjSK9 Get more breaking news at 9News.com.au: http://9Soci.al/iyCO50GjSK6

Zelenskyy urges more air defense; Russian boat hit

Ukraine Brief for Sept 3, 2025, . 538K subscribers, TVP is a Polish public broadcast service. Wikipedia, 1,623 views Sep 3, 2025

In this episode of Ukraine Brief, on the 1,288th day of Russia’s full-scale invasion, we cover another wave of Russian drone and missile strikes overnight on September 3 which struck cities in western and central Ukraine, killing one civilian, injuring several others, and causing widespread infrastructure damage. President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, speaking at the Nordic-Baltic Eight summit in Denmark, urged allies to strengthen air defenses ahead of winter. British Defence Secretary John Healey visited Kyiv for talks on military cooperation before the upcoming Ukraine Defense Contact Group meeting. Meanwhile, on the frontlines, Ukraine’s Navy destroyed a Russian speedboat in the Black Sea, and Ukrainian forces advanced in several frontline areas despite continued Russian offensives. 🔴 Watch our 24/7 livestream - https://youtube.com/live/UFrlr77yff8 Bringing you all the latest daily news and updates, TVP World is Poland's first English-language channel where you can find world news as seen from the Polish perspective and the latest news from the CEE region. Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram. https://tvpworld.com/ / tvpworldcom / tvpworld_com / tvp_world https://www.threads.net/@tvp_world https://bsky.app/profile/tvpworld.bsk... / tvpworld.com https://t.me/tvp_world

Milestones Since February 2022 to Present

These are results for milestones in ukraine conflict since February 2022 from AI. For a complete look, review the details from UK Parliament, House of Comments Library Research Briefing. Please download the file for specifics. It's an excellent read.

AI Overview

Key milestones in the Ukraine conflict since February 2022 include Russia's full-scale invasion on February 24, 2022, followed by intense fighting and Ukraine's liberation of the cities of Kharkiv and Kherson in late 2022 during a successful counteroffensive. In late 2023, a large-scale Ukrainian counteroffensive made little territorial gain, and in June 2023, the Kakhovka Dam was destroyed, impacting battle plans. Russia launched further territorial gains in 2024, particularly in the Donbas region, while Ukraine continued to engage in drone warfare and secure international aid.

Key Events and Milestones:

Russia launched a full-scale invasion from the north, east, and south, with initial attempts to capture Kyiv and other cities facing strong Ukrainian resistance.

Russian forces were repelled from Kyiv after stiff resistance.

Ukraine's first counteroffensive began, starting in the east and south of the country.

Russia illegally annexed four partially occupied Ukrainian regions: Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia.

Ukraine successfully reclaimed significant territory in the Kharkiv and Kherson regions.

Ukraine launched its anticipated second counteroffensive. The Kakhovka Dam was destroyed, which led to widespread flooding and disrupted Ukrainian efforts.

The second Ukrainian counteroffensive concluded with limited territorial changes along the front lines.

Russia gained ground, particularly in the Donbas region, and continued to bombard Ukrainian cities. Ukraine maintained drone attacks on Russian military targets and relied on significant international aid.

Three years after the full-scale invasion, Russia still occupies approximately 20% of Ukraine's territory.

UK Parliament

House of Comments Library Research Briefing

Published Friday, 22 August, 2025

This paper provides a timeline of the major events in the Ukraine-Russia conflict since the 2022 Russian invasion.

Conflict in Ukraine: A timeline (current conflict, 2022 - present) (1 MB , PDF)

The current conflict in Ukraine began on 24 February 2022 when Russian military forces entered the country from Belarus, Russia and Crimea.

Prior to the invasion, there had already been eight years of conflict in eastern Ukraine between Ukrainian Government forces and Russia-backed separatists.

This paper provides a timeline of the major events that happened in the conflict in Ukraine since the 2022 Russian invasion.

A timeline covering events during the prior eight years is available in Commons Library research briefing CBP-9476, Conflict in Ukraine: A timeline (2014 – eve of 2022 invasion).

Note: There was a change of government in the UK following the General Election on 4 July 2024. All references to the Prime Minister and other ministers, and UK government policies, are correct as of the date of each entry.

Note: On 20 January 2025 the Trump administration took office in the US. All references to the US President and cabinet secretaries, and US government policies, are correct as of the date of each entry.

Russia & Ukraine

Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment

Russian OffensioplinesThe British and French-led Coalition of the Willing and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky met in Paris to discuss possible future security guarantees for Ukraine that aim to ensure a just and lasting peace on September 4.[1] The heads of state and leaders of 35 countries and international organizations participated, including French President Emmanuel Macron, Finnish President Alexander Stubb, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz, British Prime Minister Keir Starmer, Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte, and US Special Envoy for the Middle East Steve Witkoff.

Macron stated that a strong Ukrainian military must be at the center of any postwar security guarantees. Macron stated that any security guarantees would need to involve commitments to rebuild and bolster the Ukrainian military.[2] Macron reported that the meeting participants agreed that the Coalition of the Willing’s primary objective in any potential negotiations is to ensure that Russia does not impose any limits on the size or capabilities of the Ukrainian military.[3] Macron stated that Ukraine’s allies must seek to provide Ukraine with the means to restore its military in order to deter and resist future Russian aggression.

Macron stated that 26 states formally agreed to form a “reassurance force” as part of security guarantees for postwar Ukraine. Macron stated that 26 unspecified states agreed to send ground forces to Ukraine or to provide assets to support at sea or in the sky.[4] Macron stated that the forces will be ready to deploy to Ukraine the day after Ukraine and Russia reach a ceasefire or peace agreement in the future. Macron noted that the foreign troops would not deploy to the frontline but to still undecided areas behind the front to prevent future Russian aggression.[5] Macron stated that the United States has been involved in every stage of the security guarantee process and that the Coalition of the Willing will finalize US support for European-led security guarantees in the coming days. France and the UK have previously indicated their willingness to deploy troops to postwar Ukraine.[6] Reuters reported on September 4 that a German government spokesperson stated that Germany will decide on its military engagement “in due course when the framework is clear,” including the kind and extent of US involvement and the result of the peace negotiation process.[7]

The Kremlin continues to explicitly reject any foreign troops on Ukrainian territory as part of postwar security guarantees. Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) Spokesperson Maria Zakharova stated on September 4 that Russia will not discuss “any security foreign intervention” in Ukraine “in any form, in any format.”[8] Zakharova claimed that such a foreign troop deployment is “fundamentally unacceptable.” Zakharova similarly said on August 18 that Russia “categorical[ly] reject[s]” “any scenario that envisages the appearance in Ukraine of a military contingent with the participation of NATO countries,” and Kremlin Spokesperson Dmitry Peskov claimed on August 27 that Russia takes a “negative view” of European proposals of security guarantees for Ukraine and will perceive European force deployments to postwar Ukraine as an expansion of NATO’s presence.[9] These repeated Kremlin rejections of Western security guarantees are part of Russia’s calls for it to have a veto over any Western security guarantees for Ukraine.[10] Russia also previously tried to impose severe restrictions on the size of the Ukrainian military in the 2022 Istanbul draft peace agreement, and Russia has indicated that it continues to view the 2022 Istanbul draft treaty as the basis for any future peace settlement.[11] Russia has repeatedly demonstrated that it remains committed to achieving its original war aims, including the reduction of Ukraine’s military such that Ukraine cannot defend itself against future Russian attacks.[12]

The Coalition of the Willing also outlined ways for states that are unable to deploy ground, sea, or air assets to participate in security guarantees for postwar Ukraine. Zelensky stated after the meeting that the Coalition of the Willing can also support a strong Ukrainian military with weapons provisions, training, and financing for Ukraine’s weapons production.[13] Zelensky stated that states that do not have their own forces can contribute to the security guarantees financially, including by financing Ukrainian weapons production. Starmer stated that he welcomed announcements from unspecified Coalition of the Willing partners that they plan to supply Ukraine with long-range missiles.[14] Czech Prime Minister Petr Fiala emphasized that security guarantees are necessary in order to deter Russian aggression and that the Coalition of the Willing is in agreement that Ukraine needs continued defense aid to ensure a just and lasting peace.[15] Fiala announced that Czechia will begin training Ukrainian F-16 pilots on subsonic aircraft and simulators as part of Czechia’s aid package to Ukraine. Fiala stated that Czechia will continue to supply Ukraine with ammunition.

The Coalition of the Willing discussed additional sanctions against Russia with US President Donald Trump as part of coordinated Western efforts to deny Russia funding for its war against Ukraine. Reuters reported that a White House official stated that US President Donald Trump spoke with the leaders of the Coalition of the Willing after the meeting and that Trump called on them to stop buying Russian oil as this helps fund Russia’s war machine.[16] The White House official stated that Trump also called for European leaders to put economic pressure on the People’s Republic of China (PRC) for its involvement in Russia’s war effort. Macron confirmed that the coalition spoke with Trump about sanctions and stated that the parties agreed to work more closely on future sanctions, especially those targeting Russia’s gas and energy sectors and the PRC.[17] Macron stated that Europe and the United States will impose additional sanctions against Russia if Moscow continues to refuse peace negotiations.

Russian bankers continue to express concerns over the increasingly stagnant Russian economy. Sberbank CEO and Former Russian Minister of Economic Development and Trade, German Gref, claimed on September 4 that the Russian Central Bank will likely lower its key interest rate to 14 percent by the end of 2025, but that this would not be enough to revive the Russian economy.[18] Gref called on the Central Bank to lower the key interest rate to 12 percent or less to stimulate economic growth. The Central Bank already lowered its key interest rate twice in the last three months, from a record high of 21 percent down to 20 percent in June 2025 and to 18 percent in July 2025 – likely as part of a premature effort to maintain the facade of economic stability.[19] Gref acknowledged that the Russian economy is in a ”cooling period” and that Sberbank lowered its forecast for growth in corporate lending from nine to 11 percent to seven to nine percent. Gref added that the Russian ruble will likely weaken by the end of 2025. Russia has been leveraging thestrengthened ruble to soften the blow of Western sanctions as parallel imports are cheaper and substitutes are affordable, and the Central Bank used the strengthened ruble to justify lowering its key interest rate in Summer 2025.[20] The Russian economy is already struggling with gasoline price spikes, labor shortages, and wage inflation from increased payments to sustain military recruitment and to augment the defense industrial base’s (DIB) labor force.[21] Gref’s proposal to lower the key interest rate even further to 12 percent would flood the Russian economy with money and likely weaken consumer purchasing power, devalue the ruble in the medium-to long-term, and create further macroeconomic instability in Russia.[22]

Key Takeaways

The British and French-led Coalition of the Willing and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky met in Paris to discuss possible future security guarantees for Ukraine that aim to ensure a just and lasting peace on September 4.

Macron stated that a strong Ukrainian military must be at the center of any postwar security guarantees.

Macron stated that 26 states formally agreed to form a “reassurance force” as part of security guarantees for postwar Ukraine.

The Kremlin continues to explicitly reject any foreign troops on Ukrainian territory as part of postwar security guarantees.

The Coalition of the Willing also outlined ways for states that are unable to deploy ground, sea, or air assets to participate in security guarantees for postwar Ukraine.

The Coalition of the Willing discussed additional sanctions against Russia with US President Donald Trump as part of coordinated Western efforts to deny Russia funding for its war against Ukraine.

Russian bankers continue to express concerns over the increasingly stagnant Russian economy.

Ukrainian forces advanced near Kupyansk and Siversk and in the Kostyantynivka-Druzhkivka tactical area. Russian forces advanced in northern Sumy Oblast and near VelykomykhailivkaWe do not report in detail on Russian war crimes because these activities are well-covered in Western media and do not directly affect the military operations we are assessing and forecasting. We will continue to evaluate and report on the effects of these criminal activities on the Ukrainian military and the Ukrainian population and specifically on combat in Ukrainian urban areas. We utterly condemn Russian violations of the laws of armed conflict and the Geneva Conventions and crimes against humanity even though we do not describe them in these reports.

Ukrainian Operations in The Russian Federation

Ukrainian forces may have struck two radar systems in Rostov Oblast on the night of September 3 to 4. Ukrainian military outlet Militarnyi reported that NASA Fire Information for Resource Management (FIRMS) data collected on September 4 showed heat signatures at the Russian South Navigation Radar System-1 in Rostov-on-Don and the grounds of the former Russian 1244th Anti-Aircraft Missile Regiment, which used to operate S-300PS air defense systems, near Nazarov (northeast of Rostov-on-Don).[23] Militarnyi reported that the heat signatures may indicate fires in the area. Militarnyi reported that Russian forces appear to have tried to restore the base of the 1244th Regiment for use in its war against Ukraine and that the site includes a radar station.

Russian Supporting Effort: Northern Axis

Russian objective: Create defensible buffer zones in northern Ukraine along the international border and approach to within tube artillery range of Sumy City

Russian forces recently advanced in northern Sumy Oblast.

Assessed Russian advances: Geolocated footage published September 4 indicates that Russian forces recently advanced south of Yablunivka (northeast of Sumy City).[24]

Russian forces attacked in Sumy and Kursk oblasts, including north of Sumy City near Oleksiivka, Kindrativka, and Andriivka and northeast of Sumy City near Yunakivka, on September 3 and 4.[25] Ukrainian military observer Kostyantyn Mashovets reported that Ukrainian forces successfully counterattacked near Kindrativka, Oleksiivka, and Sadky (northeast of Sumy City).[26]

Mashovets reported that Russian forces advanced about half a kilometer north of Varachyne (north of Sumy City) to the O-191504 Varachyne-Oleksiivka highway.[27]

A Russian milblogger reportedly affiliated with the Northern Grouping of Forces claimed that Ukrainian drones are reducing Russia’s manpower and equipment advantage and that Russia’s tactic of using small groups to infiltrate and accumulate in the Ukrainian near rear is not effective in the Sumy direction, as Russian forces are unable to bypass Ukrainian positions unnoticed.[28] The milblogger claimed that the Russian military command is sending Russian forces to assault Ukrainian positions across open fields on the southern outskirts of Oleksiivka. The milblogger also claimed that elements of the Russian 1427th Motorized Rifle Regiment (likely part of the 69th Motorized Rifle Division, 6th Combined Arms Army [CAA], Leningrad Military District [LMD]) are facing difficulties with the supply of ammunition and provisions near Tetkino, Kursk Oblast.[29]

Order of Battle: Elements of the Russian 83rd Separate Airborne (VDV) Brigade reportedly launched a failed assault near Varachyne (north of Sumy City).[30] Elements of the 177th Naval Infantry Regiment (Caspian Flotilla) and the 30th Motorized Rifle Regiment (72nd Motorized Rifle Division, 44th Army Corps [AC], LMD) reportedly failed to advance near Kindrativka.[31] Drone operators of the 106th VDV Division are reportedly striking Ukrainian forces near Marine (east of Sumy City).[32] Drone operators of the 137th VDV Regiment (106th VDV Division) are reportedly operating in the Sumy direction.[33] Drone operators of the 217th VDV Regiment (98th VDV Division) are reportedly striking Ukrainian forces in the Sumy direction.[34] Drone operators of the Anvar Spetsnaz Detachment (possibly referring to the BARS-25 Anvar volunteer detachment) are reportedly striking Ukrainian forces in Chernihiv and Sumy oblast border areas.[35]

Russian Main Effort: Eastern Ukraine

Russian Subordinate Main Effort #1

Russian objective: Push Ukrainian forces back from the international border with Belgorod Oblast and approach to within tube artillery range of Kharkiv City.

Russian forces continued offensive operations in northern Kharkiv Oblast on September 4 but did not make confirmed advances.

Unconfirmed claims: A Russian milblogger claimed that Russian forces advanced in eastern Vovchansk and west of Synelnykove (both northeast of Kharkiv City).[36]

Russian forces attacked northeast of Kharkiv City near Vovchansk and toward Synelnykove on September 3 and 4.[37]

Neither Ukrainian nor Russian sources reported ground activity in the Velykyi Burluk direction on September 4.

Russian Subordinate Main Effort #2

Russian objective: Capture the remainder of Luhansk Oblast and push westward into eastern Kharkhiv Oblast and encircle northern Donetsk Oblast

Ukrainian forces recently advanced in the Kupyansk direction.

Assessed Ukrainian advances: Ukrainian military observer Kostyantyn Mashovets implied on September 4 that Ukrainian forces recently regained some positions near the UkrAvtoGaz and TatNeft gas stations on the northern outskirts of Kupyansk and that elements of the Russian 6th Combined Arms Army (Leningrad Military District [LMD]) are trying to maintain their positions on the outskirts of Kupyansk near the gas stations.[38]

Unconfirmed claims: Russian milbloggers claimed that Russian forces advanced west of Myrove (northwest of Kupyansk).[39]

Russian forces attacked near Kupyansk itself, west of Kupyansk near Sobolivka, north of Kupyansk near Kindrashivka and toward Kutkivka, east of Kupyansk near Petropavlivka, and southeast of Kupyansk near Stepova Novoselivka on September 3 and 4.[40] Mashovets stated that Ukrainian forces counterattacked on the northern and western outskirts of Kupyansk.[41]

pRaion Military Administration Head Andriy Kanashevych stated on September 4 that Ukrainian aid workers are facing difficulties evacuating civilians from settlements near Kupyansk due to the danger of Russian strikes.[42] The spokesperson of a Ukrainian brigade operating in the Kupyansk direction reported that Russian forces are using anti-thermal cloaks to move alone or in pairs across the roughly one kilometer toward Ukrainian forward positions at night before concentrating and attacking.[43] The spokesperson noted that Russian iinfantry is using anti-thermal cloaks instead of motorcycles and buggies to avoid Ukrainian drone strikes.

Order of Battle: Mashovets stated that elements of the Russian 69th Motorized Rifle Division (6th CAA, LMD) are operating near Fyholivka (northeast of Kupyansk) and the Dvorichanskyi National Nature Park (north of Kupyansk).[44] Mashovets stated that elements of the 27th Motorized Rifle Brigade (1st Guards Tank Army [GTA], Moscow Military District [MMD]) and 68th Motorized Rifle Division (6th CAA, LMD) are operating near Kindrashivka.[45] Elements of the 352nd Motorized Rifle Regiment (11th Army Corps [AC], LMD) are reportedly operating near Stepova Novoselivka.[46] Drone operators of the 16th Spetsnaz Brigade (Russian General Staff’s Main Directorate [GRU]) are reportedly striking Ukrainian forces near Smorodivka (northwest of Kupyansk).[47]

Russian forces continued offensive operations in the Borova direction on September 9 but did not advance.

Russian forces attacked north of Borova toward Novoplatonivka, northeast of Borova near Zahryzove and toward Borisivka Andriivka, and southeast of Borova near Hrekivka on September 3 and 4.[48]

Russian forces continued offensive operations in the Lyman direction on September 9 but did not make confirmed advances.

Unconfirmed claims: A Russian milblogger claimed that Russian forces advanced east of Shandryholove and north of Derylove (both northwest of Lyman).[49]

Russian forces attacked northwest of Lyman near Karpivka, Serednie, and Shandryholove and toward Drobysheve; north of Lyman near Kolodyazi, Ridkodub, Novomykhailivka, and Novyi Myr; east of Lyman near Torske; and southeast of Lyman in the Serebryanske forest area and toward Yampil on September 3 and 4.[50]

Russian Subordinate Main Effort #3

Russian objective: Capture the entirety of Donetsk Oblast, the claimed territory of Russia’s proxies in Donbas, and possibly advance into Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

Note: ISW has reorganized its axes in Donetsk Oblast to better analyze and assess the Russian military command’s tactical and operational objectives east and west of Ukraine’s fortress belt. ISW combined the Chasiv Yar and Toretsk directions into the Kostyantynivka-Druzhkivka Tactical Area, given that the previously separate Chasiv Yar and Toretsk axes have now converged into a single tactical area around Kostyantynivka. ISW also created a separate Dobropillya Tactical Area, given that the Dobropillya salient is supporting operations beyond Pokrovsk in the fortress belt area of operations. ISW will continue refining its operational-tactical framework for the fortress belt as the situation evolves.

Ukrainian forces recently advanced in the Siversk direction.

Assessed Ukrainian advances: Geolocated footage published on September 4 indicates that Ukrainian forces recently advanced in northwestern Serebryanka (northeast of Siversk).[51]

Russian forces attacked near Siversk itself; northwest of Siversk toward Dronivka; northeast of Siversk near Hryhorivka and Serebryanka; southeast of Siversk near Vyimka; and southwest of Siversk toward Bondarne and Pazeno on September 3 and 4.[52] A Russian milblogger claimed that Ukrainian forces counterattacked near Perezine (south of Siversk), Fedorivka (southwest of Siversk), Vyimka, and Novoselivka (east of Siversk).[53]

Order of Battle: Ukrainian military observer Kostyantyn Mashovets reported that elements of the Russian 6th and 127th motorized rifle brigades (both of the 3rd Combined Arms Army [CAA], formerly 2nd Luhansk People’s Republic Army Corps [LNR AC], Southern Military District [SMD]) are attacking near Serebryanka and Verkhnokamyaske (east of Siversk).[54]Ukrainian forces recently advanced in the Kostyantynivka-Druzhkivka tactical area.

Assessed Ukrainian advances: Geolocated footage published on September 3 indicates that Ukrainian forces recently advanced in western Katerynivka (south of Kostyantynivka).[55]

Unconfirmed claims: Mashovets reported that Ukrainian forces continue to hold Volodymyrivka (southwest of Druzhkivka).[56]

Russian forces conducted offensive operations east of Kostyantynivka near Stupochky and Predtechyne; southeast of Kostyantynivka near Dyliivka and Oleksandro-Shultyne; south of Kostyantynivka near Shcherbynivka, Kleban-Byk, Katerynivka, Nelipivka, and Pleshchiivka; south of Druzhkivka near Rusyn Yar and Poltavka; and southwest of Druzhkivka near Volodymyrivka on September 3 and 4.[57] A Russian milblogger claimed that positional engagement is ongoing near Chasiv Yar (northeast of Kostyantynivka) and that Ukrainian forces counterattacked near Shcherbynivka.[58]

Russian milbloggers claimed that Ukrainian forces maintain positions within Shcherbynivka and Kleban-Byk.[59] A milblogger denied Russian claims that Russian forces had encircled Ukrainian forces south of the Kleban-Byk Reservoir (northwest of Kleban-Byk).[60]Order of Battle: Elements of the Russian 4th Motorized Rifle Brigade (3rd CAA, SMD) are reportedly operating in Oleksandro-Shulytne, and elements of the 103rd Motorized Rifle Regiment (150th Motorized Rifle Division, 8th CAA, SMD) are reportedly operating in Kleban-Byk.[61] Elements of the 242nd Motorized Rifle Regiment (20th Motorized Rifle Division, 8th CAA) are reportedly operating in Rusyn Yar.[62] Drone operators of the 98th Airborne (VDV) Division are reportedly striking Ukrainian forces near Chervone (northeast of Kostyantynivka).[63] Drone operators of the Afipsa Storm Battalion of the 150th Motorized Rifle Division (8th CAA) are striking Ukrainian forces north of Shcherbynivka.[64] Drone operators of the 68th Separate Reconnaissance Battalion of the 20th Motorized Rifle Division (8th CAA) are reportedly striking Ukrainian forces near Yablunivka (south of Kostyantynivka).[65] Drone operators of the 33rd Motorized Rifle Regiment(20th Motorized Rifle Division, 8th CAA) are reportedly operating in the Kostyantynivka tactical area.[66]

Russian forces continued offensive operations in the Dobropillya tactical area on September 4 but did not advance.

Russian forces conducted offensive operations northeast of Dobropillya near Kucheriv Yar; east of Dobropillya near Vilne, Shakhove, and Nove Shakhove and toward Novyi Donbas; and southeast of Dobropillya near Zapovidne and Dorozhnie on September 3 and 4.[67] A Russian milblogger claimed that Russian forces conducted a raid on the southeastern outskirts of Shakhove.[68] Another Russian milblogger claimed that Ukrainian forces counterattacked in Zapovidne.[69] Mashovets reported that Ukrainian forces continue to hold Zapovidne (southeast of Dobropillya).[70]

Order of Battle: Mashovets reported that elements of the Russian 1st, 114th, and 132nd motorized rifle brigades (all three of the 51st CAA, formerly 1st Donetsk People’s Republic [DNR] AC, SMD) are operating in the Dobropillya tactical area.[71]

Urainian forces recently advanced in the Pokrovsk direction.Assessed Ukrainian advances: Geolocated footage published on September 4 indicates that Ukrainian forces recently advanced west of Zatyshok (northeast of Pokrovsk).[72]Unconfirmed claims: A Russian milblogger claimed that Russian forces advanced toward Molodetske (southwest of Pokrovsk).[73]

Russian forces conducted offensive operations near Pokrovsk itself; north of Pokrovsk near Rodynske; northeast of Pokrovsk near Novoekonomichne, Zatyshok, Fedorivka, and Mykolaivka; east of Pokrovsk near Myrolyubivka, Promin, and Myrnohrad; southeast of Pokrovsk near Lysivka and Sukhyi Yar; south of Pokrovsk near Chunyshyne and toward Novopavlivka; and southwest of Pokrovsk near Troyanda, Udachne, Kotlyne, Zvirove, and Leontovychi and toward Molodetske on September 3 and 4.[74] A Russian milblogger claimed that Ukrainian forces counterattacked near Myrne (northeast of Pokrovsk).[75]

Ukrainian Dnipro Group of Forces Spokesperson Lieutenant Colonel Oleksiy Belskyi responded to footage online allegedly showing Russian forces trying to enter Pokrovsk through the sewer system, stating that the sewer pipes in the area are only 60 centimeters (about two feet) in diameter and that Ukrainian engineers reassured that Russian forces will not be able to use these pipes to advance due to the small diameter and waste.[76] Mashovets reported that Russian forces have not seized Krasnyi Lyman (northeast of Pokrovsk).[77] A drone pilot of a Ukrainian battalion operating in the Pokrovsk direction reported that Russian forces are striking Ukrainian ground lines of communication (GLOCs) and are having issues with logistics, forcing them to use individual soldiers and buggies to deliver ammunition to frontline positions.[78]

Order of Battle: Mashovets stated that elements of the Russian 39th Motorized Rifle Brigade (68th AC, Eastern Military District [EMD]) and 1st and 110th motorized rifle brigades (both of the 51st CAA, SMD) are attacking along the Rodynske-Bilytske line (north of Pokrovsk) and that elements of the 5th and 9th motorized rifle brigades (both of the 51st CAA) are attacking near Novoekonomichne.[79] Drone operators of the 506th Motorized Rifle Regiment (27th Motorized Rifle Division, 2nd CAA, Central Military District [CMD]) are reportedly striking Ukrainian forces near Pokrovsk.[80]

Russian forces continued offensive operations in the Novopavlivka direction on September 4 but did not advance.

Russian forces attacked east of Novopavlivka near Horikhove; south of Novopavlivka near Filiya and Yalta; and southwest of Novopavlivka near Zelenyi Hai, Tovste, and Ivanivka on September 3 and 4.[81] Russian milbloggers claimed that Ukrainian forces counterattacked near Tovste, Ivanivka, and Zelenyi Hai.[82]

A Russian milblogger claimed on September 3 that elements of the Russian 11th Air Force and Air Defense Army (Russian Aerospace Forces [VKS] and EMD) struck a bridge in Ivanivka.[83]

Order of Battle: Drone operators of the Rubikon Center for Advanced Unmanned Technologies are reportedly striking Novopavlivka, and reconnaissance elements of the 1452nd Motorized Rifle Regiment (reportedly of the 41st CAA, CMD) are reportedly identifying targets for strikes against Ukrainian forces near Novopavlivka.[84]

Russian forces recently advanced in the Velykomykhailivka direction.

Assessed Russian advances: Geolocated footage published on September 4 shows two Russian servicemembers raising a flag in Novoselivka (east of Velykomykhailivka), and ISW assesses that Russian forces seized the settlement.[85] The Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) and Russian milbloggers credited elements of the Russian 36th Motorized Rifle Brigade (29th CAA, EMD) with seizing the settlement.[86]

Unconfirmed claims: The Russian MoD claimed that the Russian Eastern Grouping of Forces seized all of Donetsk Oblast in its area of responsibility (AoR), including Oleksandrohrad (east of Velykomykhailivka).[87] Russian milbloggers claimed that Russian forces seized Khoroshe (southeast of Velykomykhailivka) and advanced north of Novoselivka, west of Oleksandrohrad, and south of Vorone (southeast of Velykomykhailivka).[88] Ukrainian Dnipro Group of Forces Spokesperson Lieutenant Colonel Oleksiy Belskyi denied claims that Russian forces seized Voskresenka (east of Velykomykhailivka).[89]

Russian forces attacked northeast of Velykomykhailivka near Andriivka-Klevstove, east of Velykomykhailivka near Voskresenka and Sichneve, and southeast of Velykomykhailivka near Komyshuvakha on September 3 and 4.[90] Russian milbloggers claimed that Ukrainian forces counterattacked near Andriivka-Klevtsove and Novoselivka.[91]

Order of Battle: Drone operators of the Russian 14th Spetsnaz Brigade (Russian General Staff’s Main Directorate [GRU]) are reportedly striking Ukrainian positions near Novoselivka.[92] Elements of the 11th Air Force and Air Defense Army (VKS, EMD) are reportedly conducting unguided glide bomb strikes against Ukrainian positions near Sosnivka (southeast of Velykomykhailivka).[93] Drone operators of the 38th Motorized Rifle Brigade (35th CAA, EMD) are reportedly operating in the Vremivka (Velykomykhailivka) direction.[94]

Russian Supporting Effort: Southern Axis

Russian objective: Maintain frontline positions, secure rear areas against Ukrainian strikes, and advance within tube artillery range of Zaporizhzhia City

Russian forces attacked in eastern Zaporizhia Oblast northeast of Hulyaipole near Olhivske and Novoivanivka on September 4 but did not advance.[95]

Russian forces continued offensive operations in western Zaporizhia Oblast on September 4 but did not advance.

Russian forces attacked south of Orikhiv near Novodanylivka, southwest of Orikhiv near Kamyanske, and west of Orikhiv near Stepnohirsk and Plavni on September 3 and 4.[96] A Russian milblogger claimed that Ukrainian forces counterattacked near Plavni.[97]

The deputy commander of a Ukrainian brigade operating in the Zaporizhia direction reported on September 4 that Russian forces are increasing their activity in the area, including by using more heavy equipment to attack Ukrainian positions, and are seriously preparing for an offensive.[98] The deputy commander reported that Russian forces first deployed first-person view (FPV) drones, including those with fiber optic cables, and reconnaissance drones to strike the Ukrainian forces at forward positions before attacking with armored vehicles. The deputy commander stated that Russian forces are advancing through the 10-kilometer “grey zone” of increased drone operations danger by first driving a trawl tank to demine and clear new routes, followed by Russian infantry advances.

Order of Battle: Elements of the Russian 7th Airborne (VDV) Division are reportedly operating near Kamyanske and Stepnohirsk.[99] Drone operators of the BARS-Sarmat Unmanned Systems Special Purpose Center (formerly BARS-Sarmat Detachment, subordinated to Airborne Forces) are reportedly striking Ukrainian forces near Stepnohirsk.[100] Drone operators of the 38th Motorized Rifle Brigade (35th Combined Arms Army [CAA], Eastern Military District [EMD]), elements of the Nemets group of the 291st Motorized Rifle Regiment (42nd Motorized Rifle Division, 58th CAA, Southern Military District [SMD]), and electronic warfare (EW) elements of the 74th Motorized Rile Regiment (reportedly of the 58th CAA, SMD) are reportedly operating in the Zaporizhia direction.[101]

Russian forces continued offensive operations in the Kherson direction, including east of Kherson City near Antonivka, on September 3 and 4, but did not advance.[102]

Russian Air, Missile, and Drone Campaign

Russian Objective: Target Ukrainian military and civilian infrastructure in the rear and on the frontline

Russian forces conducted a series of drone strikes against Ukraine on the night of September 3 to 4. The Ukrainian Air Force reported that Russian forces launched 112 Shahed-type and decoy drones from the directions of Kursk, Oryol, and Bryansk cities; Millerovo, Rostov Oblast; Primorsko-Akhtarsk, Krasnodar Krai; and occupied Hvardiiske, Crimea.[103] The Ukrainian Air Force reported that Ukrainian air defenses downed 84 drones. The Ukrainian Air Force reported that 28 drones struck 17 locations and that debris fell in five locations. Ukrainian officials reported that Russian strikes damaged civilian infrastructure in Kharkiv and Odesa oblasts.[104]

Russian forces conducted a missile strike against a Ukrainian humanitarian mission in Chernihiv Oblast on September 4. The Ukrainian Main Directorate of the National Police in Chernihiv Oblast reported that Russian forces conducted a missile strike against a humanitarian demining mission near Chernihiv City.[105] Geolocated footage published on September 4 shows an explosion near civilian vehicles near Chernihiv City.[106] Chernihiv Oblast Military Administration Head Vyacheslav Chaus reported that the strike killed two humanitarian workers.[107]

Significant Activity in Belarus

Russian efforts to increase its military presence in Belarus and further integrate Belarus into Russian-favorable frameworks

Nothing Significant To Report.

Let's take a deep dive into the war in Ukraine, but first why does Trump support Putin instead of Volodymyr Zelensky and our allies since WWII?

AI Overview

Commentators, political analysts, and foreign policy experts have offered several reasons for Donald Trump's past and present alignment with Russian leader Vladimir Putin, often prioritizing this relationship over traditional U.S. alliances

. These interpretations, which are not mutually exclusive, point to a mix of personal admiration for authoritarian strength, an "America First" foreign policy philosophy, and transactional negotiating tactics.

Personal admiration for strong leaders

Perceived strength: Trump has repeatedly praised Putin as a "strong" and "savvy" leader, suggesting an affinity for strongman or authoritarian figures. This differs from his view of many democratically elected leaders, whom he has at times treated with open contempt.

Rejection of democratic norms: Some observers suggest Trump's approach aligns with Putin's throwback view of international relations, where powerful nations exert control over smaller states, and the existing world order is seen as unfair to non-Western powers.

Opacity in their relationship: The personal chemistry between Trump and Putin has been described as opaque, dating back to their interactions before and during Trump's first presidency. Key incidents, such as their closed-door meeting in Helsinki, fueled public skepticism about Trump's willingness to hold Putin accountable.

"America First" and transactional diplomacy

Disdain for traditional alliances: A core tenet of Trump's foreign policy is a skepticism toward long-standing U.S. alliances like NATO, viewing them as financially draining to the U.S. This aligns with his broader "America First" platform, which prioritizes bilateral deals and perceived national interests over multinational cooperation.

Desire for a "deal": Trump has long framed his interactions with Russia in the context of striking a deal. He has repeatedly stated his belief that getting along with Moscow is in the U.S. national interest and has positioned himself as a potential mediator in conflicts like the war in Ukraine.

Leverage and unpredictability: Some analysts suggest Trump uses negotiations, and withholding punitive measures like sanctions, as leverage to force a deal. This approach, however, is often criticized for undermining U.S. positions and creating incoherence in foreign policy.

Domestic political considerations

Campaign rhetoric and populist appeal: Trump's rhetoric often plays on populist sentiments, casting doubt on establishment institutions and traditional foreign policy approaches. His comments about Russia have at times been used to criticize his political opponents and undermine investigations into Russian interference.

Shifting stances based on political winds: While Trump has often appeared sympathetic to Putin, his public statements have sometimes grown more frustrated when a deal fails to materialize, particularly in the context of the war in Ukraine. These shifts may reflect a desire to position himself favorably depending on political circumstances.

Critiques and recent developments.

So apparently Trump’s been chasing Putin's approval like the last rose on The Bachelor,

but surprise, surprise — Vlad isn’t exactly returning the energy. Reports say Trump’s

frustrated, especially about the whole Ukraine situation not magically disappearing.

Meanwhile, critics are like, “Cool, but you’re still wrecking NATO and clowning around with democracy, thanks.”

And then — oh lord — he literally rolled out the red carpet in Alaska. Alaska! Like it’s the Oscars for

dictators. Honestly, I’m embarrassed for us as Americans. My dad fought in WWII, my uncle was a

POW — and this guy’s out here fangirling for Putin. It’s insulting.

Here’s my theory: Trump just wants to dunk on Zelensky because of the “Russia Hoax” and his first impeachment. Pure ego. Pure vengeance. Honestly, I think Trump is basically a Russian asset at this point. Putin’s dangling “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” over his head, and Trump’s dancing. Plus, Putin is disgustingly rich and just… wins every election in Russia by, you know, murdering anyone who dares run against him. That’s the kind of “strongman power” Trump dreams about with his little shriveled Grinch heart.

Except — reminder — even the Grinch’s heart grew three sizes. Trump’s? Still two sizes too small.

And yeah, I agree with the AI summary — he absolutely doesn’t get norms. NATO? He thinks it’s like a gym membership he can cancel. As for Hitler — it’s clear he admires him, and while I don’t think Trump’s personally obsessed with hating Jewish people, he sure has a thing against brown and black people. And don’t get him started on languages — the man can barely handle English, so no surprise he despises anyone bilingual.

Anyway, buckle up — next we’re diving into the actual war.

History of the Conflict

Ukraine: Conflict at the Crossroads of Europe and Russia

Ukraine’s Westward drift since independence has been countered by the sometimes violent tug of Russia, felt most recently with Putin’s 2022 invasion.

A protester sits on a monument in Kyiv during clashes with riot police in February 2014. Louisa Gouliamaki/AFP/Getty

Written By Jonathan Master Last updated February 14, 2023 7:00 am (EST)

Summary

Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has set alight the bloodiest conflict in Europe since World War II.

A former Soviet republic, Ukraine had deep cultural, economic, and political bonds with Russia, but the war could irreparably harm their relations.

Some experts view the Russia-Ukraine war as a manifestation of renewed geopolitical rivalry between major world powers.

Introduction

Ukraine has long played an important, yet sometimes overlooked, role in the global security order. Today, the country is on the front lines of a renewed great-power rivalry that many analysts say will dominate international relations in the decades ahead.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 marked a dramatic escalation of the eight-year-old conflict that began with Russia’s annexation of Crimea and signified a historic turning point for European security. A year after the fighting began, many defense and foreign policy analysts cast the war as a major strategic blunder by Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Many observers see little prospect for a diplomatic resolution in the months ahead and instead acknowledge the potential for a dangerous escalation, which could include Russia’s use of a nuclear weapon. The war has hastened Ukraine’s push to join Western political blocs, including the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Related

Why NATO Has Become a Flash Point With Russia in Ukraine

Why is Ukraine a geopolitical flash point?

Ukraine was a cornerstone of the Soviet Union, the archrival of the United States during the Cold War. Behind only Russia, it was the second-most-populous and -powerful of the fifteen Soviet republics, home to much of the union’s agricultural production, defense industries, and military, including the Black Sea Fleet and some of the nuclear arsenal. Ukraine was so vital to the union that its decision to sever ties in 1991 proved to be a coup de grâce for the ailing superpower.

In its three decades of independence, Ukraine has sought to forge its own path as a sovereign state while looking to align more closely with Western institutions, including the EU and NATO. However, Kyiv struggled to balance its foreign relations and to bridge deep internal divisions. A more nationalist, Ukrainian-speaking population in western parts of the country generally supported greater integration with Europe, while a mostly Russian-speaking community in the east favored closer ties with Russia.

Sources: CIA World Factbook; World Bank.

Ukraine became a battleground in 2014 when Russia annexed Crimea and began arming and abetting separatists in the Donbas region in the country’s southeast. Russia’s seizure of Crimea was the first time since World War II that a European state annexed the territory of another. More than fourteen thousand people died in the fighting in the Donbas between 2014 and 2021, the bloodiest conflict in Europe since the Balkan Wars of the 1990s. The hostilities marked a clear shift in the global security environment from a unipolar period of U.S. dominance to one defined by renewed competition between great powers [PDF].

In February 2022, Russia embarked on a full-scale invasion of Ukraine with the aim of toppling the Western-aligned government of Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

What are Russia’s broad interests in Ukraine?

Russia has deep cultural, economic, and political bonds with Ukraine, and in many ways Ukraine is central to Russia’s identity and vision for itself in the world.

Family ties. Russia and Ukraine have strong familial bonds that go back centuries. Kyiv, Ukraine’s capital, is sometimes referred to as “the mother of Russian cities,” on par in terms of cultural influence with Moscow and St. Petersburg. It was in Kyiv in the eighth and ninth centuries that Christianity was brought from Byzantium to the Slavic peoples. And it was Christianity that served as the anchor for Kievan Rus, the early Slavic state from which modern Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarussians draw their lineage.

Russian diaspora. Approximately eight million ethnic Russians were living in Ukraine as of 2001, according to a census taken that year, mostly in the south and east. Moscow claimed a duty to protect these people as a pretext for its actions in Crimea and the Donbas in 2014.

Superpower image. After the Soviet collapse, many Russian politicians viewed the divorce with Ukraine as a mistake of history and a threat to Russia’s standing as a great power. Losing a permanent hold on Ukraine, and letting it fall into the Western orbit, would be seen by many as a major blow to Russia’s international prestige. In 2022, Putin cast the escalating war with Ukraine as a part of a broader struggle against Western powers he says are intent on destroying Russia.

Crimea. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev transferred Crimea from Russia to Ukraine in 1954 to strengthen the “brotherly ties between the Ukrainian and Russian peoples.” However, since the fall of the union, many Russian nationalists in both Russia and Crimea longed for a return of the peninsula. The city of Sevastopol is home port for Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, the dominant maritime force in the region.

Trade. Russia was for a long time Ukraine’s largest trading partner, although this link withered dramatically in recent years. China eventually surpassed Russia in trade with Ukraine. Prior to its invasion of Crimea, Russia had hoped to pull Ukraine into its single market, the Eurasian Economic Union, which today includes Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan.

Energy. Moscow relied on Ukrainian pipelines to pump its gas to customers in Central and Eastern Europe for decades, and it paid Kyiv billions of dollars per year in transit fees. The flow of Russian gas through Ukraine continued in early 2023 despite the hostilities between the two countries, but volumes were reduced and the pipelines remained in serious jeopardy.

Political sway. Russia was keen to preserve its political influence in Ukraine and throughout the former Soviet Union, particularly after its preferred candidate for Ukrainian president in 2004, Viktor Yanukovych, lost to a reformist competitor as part of the Orange Revolution popular movement. This shock to Russia’s interests in Ukraine came after a similar electoral defeat for the Kremlin in Georgia in 2003, known as the Rose Revolution, and was followed by another—the Tulip Revolution—in Kyrgyzstan in 2005. Yanukovych later became president of Ukraine, in 2010, amid voter discontent with the Orange government.

What triggered Russia’s moves in Crimea and the Donbas in 2014?

It was Ukraine’s ties with the EU that brought tensions to a head with Russia in 2013–14. In late 2013, President Yanukovych, acting under pressure from his supporters in Moscow, scrapped plans to formalize a closer economic relationship with the EU. Russia had at the same time been pressing Ukraine to join the not-yet-formed EAEU. Many Ukrainians perceived Yanukovych’s decision as a betrayal by a deeply corrupt and incompetent government, and it ignited countrywide protests known as Euromaidan.

Putin framed the ensuing tumult of Euromaidan, which forced Yanukovych from power, as a Western-backed “fascist coup” that endangered the ethnic Russian majority in Crimea. (Western leaders dismissed this as baseless propaganda reminiscent of the Soviet era.) In response, Putin ordered a covert invasion of Crimea that he later justified as a rescue operation. “There is a limit to everything. And with Ukraine, our western partners have crossed the line,” Putin said in a March 2014 address formalizing the annexation.

Putin employed a similar narrative to justify his support for separatists in southeastern Ukraine, another region home to large numbers of ethnic Russians and Russian speakers. He famously referred to the area as Novorossiya (New Russia), a term dating back to eighteenth-century imperial Russia. Armed Russian provocateurs, including some agents of Russian security services, are believed to have played a central role in stirring the anti-Euromaidan secessionist movements in the region into a rebellion. However, unlike Crimea, Russia continued to officially deny its involvement in the Donbas conflict until it launched its wider invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Why did Russia launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022?

Some Western analysts see Russia’s 2022 invasion as the culmination of the Kremlin’s growing resentment toward NATO’s post–Cold War expansion into the former Soviet sphere of influence. Russian leaders, including Putin, have alleged that the United States and NATO repeatedly violated pledges they made in the early 1990s to not expand the alliance into the former Soviet bloc. They view NATO’s enlargement during this tumultuous period for Russia as a humiliating imposition about which they could do little but watch.

In the weeks leading up to NATO’s 2008 summit, President Vladimir Putin warned U.S. diplomats that steps to bring Ukraine into the alliance “would be a hostile act toward Russia.” Months later, Russia went to war with Georgia, seemingly showcasing Putin’s willingness to use force to secure his country’s interests. (Some independent observers faulted Georgia for initiating the so-called August War but blamed Russia for escalating hostilities.)

Despite remaining a nonmember, Ukraine grew its ties with NATO in the years leading up to the 2022 invasion. Ukraine held annual military exercises with the alliance and, in 2020, became one of just six enhanced opportunity partners, a special status for the bloc’s closest nonmember allies. Moreover, Kyiv affirmed its goal to eventually gain full NATO membership.

In the weeks leading up to its invasion, Russia made several major security demands of the United States and NATO, including that they cease expanding the alliance, seek Russian consent for certain NATO deployments, and remove U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe. Alliance leaders responded that they were open to new diplomacy but were unwilling to discuss shutting NATO’s doors to new members.

“While in the United States we talk about a Ukraine crisis, from the Russian standpoint this is a crisis in European security architecture,” CFR’s Thomas Graham told Arms Control Today in February 2022. “And the fundamental issue they want to negotiate is the revision of European security architecture as it now stands to something that is more favorable to Russian interests.”

Other experts have said that perhaps the most important motivating factor for Putin was his fear that Ukraine would continue to develop into a modern, Western-style democracy that would inevitably undermine his autocratic regime in Russia and dash his hopes of rebuilding a Russia-led sphere of influence in Eastern Europe. “[Putin] wants to destabilize Ukraine, frighten Ukraine,” writes historian Anne Applebaum in the Atlantic. “He wants Ukrainian democracy to fail. He wants the Ukrainian economy to collapse. He wants foreign investors to flee. He wants his neighbors—in Belarus, Kazakhstan, even Poland and Hungary—to doubt whether democracy will ever be viable, in the longer term, in their countries too.”

What are Russia’s objectives in Ukraine?

Putin’s Russia has been described as a revanchist power, keen to regain its former power and prestige. “It was always Putin’s goal to restore Russia to the status of a great power in northern Eurasia,” writes Gerard Toal, an international affairs professor at Virginia Tech, in his book Near Abroad. “The end goal was not to re-create the Soviet Union but to make Russia great again.”

By seizing Crimea in 2014, Russia solidified its control of a strategic foothold on the Black Sea. With a larger and more sophisticated military presence there, Russia can project power deeper into the Mediterranean, Middle East, and North Africa, where it has traditionally had limited influence. Some analysts argue that Western powers failed to impose meaningful costs on Russia in response to its annexation of Crimea, which they say only increased Putin’s willingness to use military force in pursuit of his foreign policy objectives. Until its invasion in 2022, Russia’s strategic gains in the Donbas were more fragile. Supporting the separatists had, at least temporarily, increased its bargaining power vis-à-vis Ukraine.

In July 2021, Putin authored what many Western foreign policy experts viewed as an ominous article explaining his controversial views of the shared history between Russia and Ukraine. Among other remarks, Putin described Russians and Ukrainians as “one people” who effectively occupy “the same historical and spiritual space.”

Throughout that year, Russia amassed tens of thousands of troops along the border with Ukraine and later into allied Belarus under the auspices of military exercises. In February 2022, Putin ordered a full-scale invasion, crossing a force of some two hundred thousand troops into Ukrainian territory from the south (Crimea), east (Russia), and north (Belarus), in an attempt to seize major cities, including the capital Kyiv, and depose the government. Putin said the broad goals were to “de-Nazify” and “de-militarize” Ukraine.

However, in the early weeks of the invasion, Ukrainian forces marshaled a stalwart resistance that succeeded in bogging down the Russian military in many areas, including in Kyiv. Many defense analysts say that Russian forces have suffered from low morale, poor logistics, and an ill-conceived military strategy that assumed Ukraine would fall quickly and easily.

In August 2022, Ukraine launched a major counteroffensive against Russian forces, recapturing thousands of square miles of territory in the Kharkiv and Kherson regions. The campaigns marked a stunning setback for Russia. Amid the Russian retreat, Putin ordered the mobilization of some three hundred thousand more troops, illegally annexed four more Ukrainian regions, and threatened to use nuclear weapons to defend Russia’s “territorial integrity.”

Fighting in the subsequent months focused along various fronts in the Donbas, and Russia adopted a new tactic of targeting civilian infrastructure in several distant Ukrainian cities, including Kyiv, with missile and drone strikes. At the first-year mark of the war, Western officials estimated that more than one hundred thousand Ukrainians had been killed or wounded, while Russian losses were likely even higher, possibly double that figure. Meanwhile, some eight million refugees had fled Ukraine, and millions more were internally displaced. Ahead of the spring thaw, Ukraine’s Western allies pledged to send more-sophisticated military aid, including tanks. Most security analysts see little chance for diplomacy in the months ahead, as both sides have strong motives to continue the fight.

Russia’s Annexations in Eastern Ukraine

Source: Institute for the Study of War and American Enterprise Institute.

What have been U.S. priorities in Ukraine?

Immediately following the Soviet collapse, Washington’s priority was pushing Ukraine—along with Belarus and Kazakhstan—to forfeit its nuclear arsenal so that only Russia would retain the former union’s weapons. At the same time, the United States rushed to bolster the shaky democracy in Russia. Some prominent observers at the time felt that the United States was premature in this courtship with Russia, and that it should have worked more on fostering geopolitical pluralism in the rest of the former Soviet Union.

Former U.S. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, in Foreign Affairs in early 1994, described a healthy and stable Ukraine as a critical counterweight to Russia and the lynchpin of what he advocated should be the new U.S. grand strategy after the Cold War. “It cannot be stressed strongly enough that without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be an empire, but with Ukraine suborned and then subordinated, Russia automatically becomes an empire,” he wrote. In the months after Brzezinski’s article was published, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Russia pledged via the Budapest Referendum to respect Ukraine’s independence and sovereignty in return for it becoming a nonnuclear state.

Twenty years later, as Russian forces seized Crimea, restoring and strengthening Ukraine’s sovereignty reemerged as a top U.S. and EU foreign policy priority. Following the 2022 invasion, U.S. and NATO allies dramatically increased defense, economic, and humanitarian assistance to Ukraine, as well as ramped up their sanctions on Russia. However, Western leaders have been careful to avoid actions they believe will draw their countries into the war or otherwise escalate it, which could, in the extreme, pose a nuclear threat.

What are U.S. and EU policy in Ukraine?

The United States remains committed to the restoration of Ukraine’s territorial integrity and sovereignty. It does not recognize Russia’s claims to Crimea or the other regions unlawfully annexed by Russia. Prior to the 2022 invasion, the United States supported a settlement of the Donbas conflict via the Minsk agreements [PDF].

Western powers and their partners have taken many steps to increase aid to Ukraine and punish Russia for its 2022 offensive. As of February 2023, the United States has provided Ukraine more than $50 billion in assistance, which includes advanced military aid, such as rocket and missile systems, helicopters, drones, and tanks. Several NATO allies are providing similar aid.

Meanwhile, the international sanctions on Russia have vastly expanded, covering much of its financial, energy, defense, and tech sectors and targeting the assets of wealthy oligarchs and other individuals. The U.S. and some European governments also banned some Russian banks from the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, a financial messaging system known as SWIFT; placed restrictions on Russia’s ability to access its vast foreign reserves; and blacklisted Russia’s central bank. Moreover, many influential Western companies have shuttered or suspended operations in Russia. The Group of Eight, now known as the Group of Seven, suspended Russia from its ranks indefinitely in 2014.

The invasion also cost Russia its long-awaited Nord Stream 2 pipeline after Germany suspended its regulatory approval in February. Many critics, including U.S. and Ukrainian officials, opposed the natural gas pipeline during its development, claiming it would give Russia greater political leverage over Ukraine and the European gas market. In August, Russia indefinitely suspended operations of Nord Stream 1, which provided the European market with as much as a third of its natural gas.

What do Ukrainians want?

Russia’s aggression in recent years has galvanized public support for Ukraine’s Westward leanings. In the wake of Euromaidan, the country elected as president the billionaire businessman Petro Poroshenko, a staunch proponent of EU and NATO integration. In 2019, Zelensky defeated Poroshenko in a sign of the public’s deep dissatisfaction with the political establishment and its halting battle against corruption and an oligarchic economy.

Before the 2022 offensive, polls indicated that Ukrainians held mixed views on NATO and EU membership. More than half of those surveyed (not including residents of Crimea and the contested regions in the east) supported EU membership, while 40 to 50 percent were in favor of joining NATO.

Just days after the invasion, President Zelenskyy requested that the EU put Ukraine on a fast track to membership. The country became an official candidate in June 2022, but experts caution that the membership process could take years. In September of that year, Zelenskyy submitted a formal application for Ukraine to join NATO, pushing for an accelerated admission process for that bloc as well. Many Western analysts say that, similar to Ukraine’s EU bid, NATO membership does not seem likely in the near term.

Russia & Ukraine: A history of rivalry?

d (TRT is a Turkish public broadcast service), Wikipedia, 242,601 views Feb 26, 2022 #Russians #UkrainevsRussia #Ukrainians

Two neighbours who share the same ancestry, nearly the same language and follow the same church find themselves at each other's necks. We explain how Russia and Ukraine, two brotherly nations have descended into an inevitably recurring conflict threatening global peace and security. #UkrainevsRussia #Ukrainians #Russians

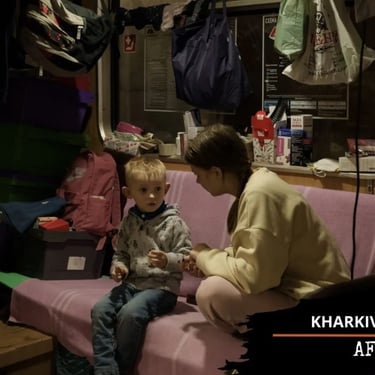

Ukraine Before and After February 24, 2022

Before February 24, 2022, Ukrainians enjoyed the freedoms of living in a democracy. They went to work and school. They spent holidays at local tourist spots or in Western European countries. They arm wrestled, played in trees and practiced dance steps in the park. They walked their streets without fear.

After February 24, 2022 — the date when Ukrainians awoke to the nightmare of Russia’s full-scale, illegal invasion — daily life became difficult. Some citizens risked their lives to leave, too often saying farewell to loved ones for the very last time. Many stayed. Families sheltered from bombs in basements and underground stations. Young men and women took up arms to defend their homeland.

While Russia’s illegal war has caused injury or death to civilians and destroyed infrastructure, it has not weakened Ukrainians’ resolve to preserve their dignity, sovereignty and democracy.

These photos do not feature the same person twice but evoke similar situations before and after the February 24 invasion.

The world recognizes Ukraine as an independent nation. Nations in Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas have joined the United States in pledging their support to Ukraine. To people the world over, the blue and yellow colors of the Ukrainian flag symbolize brave resistance.

On February 25, 2022, the day after Russia’s full-scale illegal invasion began, Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy went out on the streets of Kyiv and said, “The president is here. We are all here. Our soldiers are here.”

It has been two years, and Ukrainians stand tall — undefeated, unbowed, unyielding.